Apr 28, 2015 / By: Michael Spielman

Category: Miscellaneous

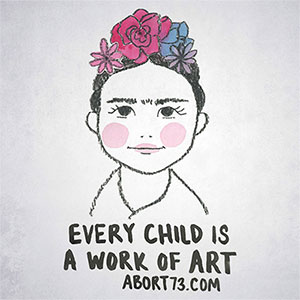

Every Child is a Work of Art. That's the message behind Abort73's newest shirt design. The culturally astute will notice a nod to Frida Kahlo—the iconic feminist artist who made a career for herself painting selfies. Like so many other famous artists, Kahlo is far more popular now than she ever was in her own lifetime. Susan Fisher Sterling, Director of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) notes that Kahlo is a perfect fit for today's "narcissistic body culture"—one that is "obsessed with ourselves and sexuality." Stephanie Mencimer, a former editor of Washington Monthly who now writes for Mother Jones, adds:

Kahlo's Communism--now treated as somehow sort of quaint--led her to embrace some unforgivable political positions… Less scandalous but worth noting is that Kahlo despised the very gringos who now champion her work, and her art reflects her obvious disdain for the United States. One wonders what the postal service was thinking when it put Kahlo on a stamp…

With that in mind, Frida Kahlo may seem a strange figure for Abort73 to lean on. In fact, it's a connection I never would have thought of myself, but that's the beauty of collaboration! "Every Child is a Work of Art" is a phrase I'd been sitting on for at least a few months. I'd given some thought to design possibilities but was fairly convinced it needed the artistic stylings of someone else. I just didn't know who that someone would be! Thankfully, that question was answered in January when I received an email from Tori Higa—an artist and illustrator from Southern California.

The email was about a poem she'd written in response to Love the Least. Her email said nothing of her illustrative abilities, but after looking through her website, I thought Tori would be a great fit for the #everychild design. It turns out she was! When the initial concept came back to me, it bore the unmistakable markings of Frida: dark hair worn up, bright flowers, and a unibrow! Tori worried the submission might be too much of an "art nerd concept," but I warmed to it quickly. Of course, as a Fine Arts major myself—who sat through more art history lectures than I'd care to remember, I suppose I am an art nerd.

So, what was it that drew me to Tori's concept? Essentially, there were three things. First, Frida Kahlo was an artist who challenged the conventional notion of beauty, both in her artwork and her person. "Kahlo not only didn't pluck her unibrow or mustache," Mencimer writes, "she groomed them with special tools and even penciled them darker." Our new shirt could have depicted a cherubic baby with fair-hair and fair-skin, but that would simply accommodate a stereotypically-narrow, Nordic notion of beauty. The message here is that children of all colors, all races, and all ethnicities are beautiful—whether they look like Romeo Beckham or not.

Second, Frida Kahlo lived most of her life with disability and made it a centerpiece of her art. Polio plagued her as a child, and a bus accident broke her body to pieces as she was entering adulthood. Doctors never expected her to live, let alone walk. But she did. And were it not for that terrible accident, it's almost certain that Frida Kahlo would never have become a painter. In her mind, an artist had to suffer to be great, and she did! Today, abortion is used as a tool to eliminate disability by eliminating the disabled. When unborn children are diagnosed with spina bifida or down syndrome, the majority of them are simply killed in the womb. Frida shows us that broken can be beautiful—that disability need not constrain someone to a dull and colorless life.

Finally, abortion was the emotional backdrop for much of Frida Kahlo's artwork. During the course of her tumultuous marriage with famed muralist Diego Rivera, Kahlo became pregnant at least three times, but none of her children were born alive. The precise reasons for these failed pregnancies are hard to come by. Some accounts call them miscarriages; others report them as abortions—though abortion itself is a historically imprecise term. Spontaneous abortion is the medical classification for miscarriage; therapeutic abortion refers to the intentional, medically- or surgically-induced procedure we associate with the word today. In Kahlo's case, medical necessity further clouds the picture.

By most accounts, the bus accident that punctured Kahlo's uterus and fractured her pelvis, left her body ill-equipped to carry a pregnancy to term. Her 1930 abortion is said to have resulted from the baby being incorrectly positioned within her compromised pelvis. In 1934, the rationale was "infantilism of the ovaries." Sandwiched between these two pregnancies was a four-year stint in the United States as her husband painted in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York. During that period, Kahlo suffered the 1932 miscarriage that spawned the work, "Henry Ford Hospital." In it, she lies naked on a hospital bed as an oversized baby hovers above her—along with a broken pelvis and a fairly scientific rendering of the female reproductive system. Other works from that same year, including "Birth of My Birth" and a lithograph simply titled "The Abortion," give further vent to Kahlo's tormented soul.

Dr. Fernando Antelo, a surgical pathologist at the Harbor UCLA Medical Center who recently researched the cause of Kahlo's failed pregnancies writes:

A very common theme in [Kahlo's] work was fertility, fertility, fertility… In one painting, she draws pelvic bones. In another, a uterus is directly drawn. Another is showing the fetus. She's telling us what she's thinking about, but she never put her finger on what exactly was wrong.

According to Mencimer, Kahlo's "images of childbirth and pregnancy are some of the most violent and disturbing ever to grace a canvas… Never before had a woman put such agonized poetry on canvas as Frida did at this time in Detroit." Historians are divided over Kahlo's level of maternal grief. Some believe her inability to have children was a devastating blow—as indicated by the private letters she sent her physician. Others believe Kahlo's grief was largely manufactured to better fit the narrative she was creating for herself: Frida Kahlo as martyr. The fact that Frida kept a pickled fetus in a jar on her mantle, and casually introduced it to others as her stillborn child, doesn't quite fit the grieving mother stereotype.

In either case, Kahlo's work connects to the issue of abortion—both implicitly and explicitly—in ways I've never seen before or since. Were Frida alive today, I don't know what her opinion of abortion would be, but it might surprise some people. She was certainly non-comformist. Though Kahlo has become "a poster child for every possible politically correct cause"—as Mencimer notes, few people bother to go below the surface. Frida historian Margaret Lindauer writes that if feminists took a closer look at her artwork, they would be far "less comfortable buying her fridge magnets." Unyielding devotion to a womanizing husband, frequent attempts at suicide, and a crippling addiction to drugs and alcohol are all cited as challenges to Kahlo's liberated feminist credentials. Could Frida's miscarriages and/or abortions have been a contributing factor to her psychological demise? It's certainly possible.

Frida Kahlo may have been a radical leftist who took extreme liberties with the marriage bed, but she was also a beautiful and talented woman—made in the image of God—who struggled to survive in a broken and violent world. In referencing Kahlo's likeness on behalf of a politically incorrect cause, my hope is to continue her legacy of challenging perceptions and turning stereotypes on their head. You may look at our new design and see nothing but a cute little girl; I see an opportunity for dialogue and introspection—with a cautiously optimistic nod to the future. You see, the girl in our design departs from the woman who inspired her in one significant way. Whereas Kahlo's visage is always dark, stern and stoic, our little girl has the hint of a smile on her lips. Whatever Frida believed, whatever you believe, every child is a work of art, and every child is hardwired for happiness. By the grace of God, it takes very little to make them smile!

Michael Spielman is the founder and director of Abort73.com. Subscribe to Michael's Substack for his latest articles and recordings. His book, Love the Least (A Lot), is available as a free download. Abort73 is part of Loxafamosity Ministries, a 501c3, Christian education corporation. If you have been helped by the information available at Abort73.com, please consider making a donation.